Viewing: SAR

October 24, 2019

Starting Science, Short Answer Responses, and more!

Someone asked me last week what my favorite subject to teach was. I’ve been asked that numerous times, and I think it’s one of the hardest things to answer. I love teaching reading, because books allow us to take a (metaphorical) field trip to new places, new times, and new situations, and to talk about each one. I love talking about what we read! I love teaching math, because it’s fascinating to see how skills can build on one another, and that’s where I tend to see kids have those “lightbulb” a-ha moments most often. Science is a real passion of mine, and I absolutely love seeing kids draw their own conclusions in class. (I’m also biased, because I wrote three of our four science units in fourth grade, so I know the lessons well and feel a sense of pride.) It’s at this point that I realize that I’ve given a snub to writing and social studies, and I quickly scamper to explain that I love those too, and I end up just saying that I love teaching everything. Perhaps it changes from day to day – and today, it was all about science!

The kids are SO excited to share their science projects with the class, which I was thrilled to see. We only got through two projects today, and the kids know that it will take several days to have everyone share. Today’s creative presentations taught us about the scientific properties of apples and apple trees, as well as about the effervescent qualities of Polident tabs. We continued the science theme of the day and kicked off our first science unit, which is all about energy. Today, we learned about electrical energy and how static electricity flows from negative to positive. We teamed up with Mrs. Matos’s class, which we’ll do from time to time throughout the year.

We’ve kicked off our first science unit today with Mrs. Matos’s class! We’re learning about energy, and today, we started by learning how electricity flows in a circuit. #AskYourKid why we couldn’t take a wire and put a light at one end and a battery at the other. More tomorrow! pic.twitter.com/bEMuthNzXs

— Jon Moss (@MossTeaches) October 24, 2019

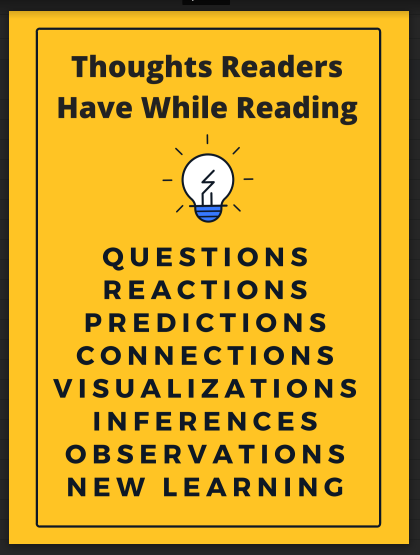

That’s not all, however! In reading, we’ve learned about the eight kinds of thoughts readers have while reading. I encourage kids to be aware of when these thoughts pop into their head, because these are what allow us to have rich discussions about what we read. These will be critical for when we launch book clubs in the late fall or winter.

We’ve moved on, in reading, to beginning our study of narrative elements. We’re going slowly (right now), because this is also our launch into short answer responses (SAR). Kids have been doing this for years, and each year, the expectations mature a bit. We drafted a SAR about the setting of the WONDERFUL book The Purple Coat, and students are working with partners to identify and explain the setting of the book The Josefina Story Quilt.

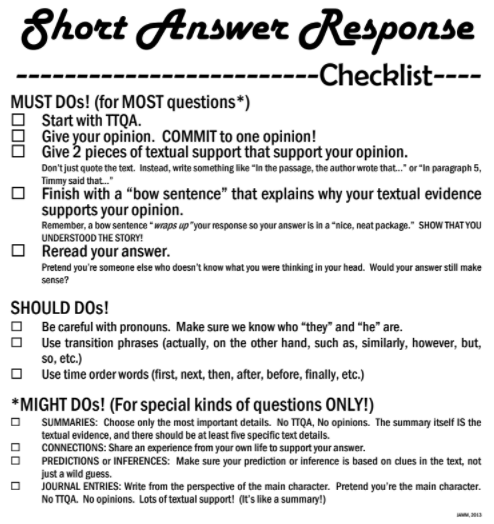

This week, we looked at the SAR checklist, which helps the students to learn what goes into a quality short answer response. TTQA stands for “Turn the Question Around”. A bow sentence shows how the textual evidence connects to the reader’s opinion. For example, if I wrote “Miss Viola Swamp was a talented teacher. I know this because she was very strict and yelled at the kids.” you might wonder why her yelling supported the idea that she was a good teacher. (Nowadays, we tend to frown on teachers who yell too much!) But if I added the sentence “The class was really wild, and she was the only person who could get them calmed down and working hard to learn.” you might better see the connection. That’s what a Bow Sentence does. The rest of these are probably more clear to you. We’ll be using this document a lot this year, and I’ll be sending home copies soon.

The Ice Cream Rubric doesn’t rate any ice cream cones. Instead, it focuses on how we assess a student’s short answer response. In class, we talked about this rubric’s value as more than something that helps to yield a grade. It helps students to know what a strong response looks like and helps them to evaluate their own work. Again, I have copies of this which will be sent home in the coming weeks.

In math, we’ve finished the first unit (as you know), and the math assessments will come home early next week. (I’d like you to sign and return them, and since I want to give you a few days to do that, I didn’t want to go over the weekend.) Right now, students are doing a great job learning about factors and multiples.

We’ve started learning about map skills, focusing on cardinal directions, latitude, and longitude. My class last year was kind enough to purchase us a dry erase globe, which has been a GREAT resource for introducing these skills.

More to come! As always, feel free to contact me with any questions.

Posted in Class Updates|By Jon Moss

November 14, 2018

How Written Responses Are Evaluated

With report cards going live this morning and parent conferences kicking off tomorrow afternoon, I wanted to take a moment to encourage you to visit your child’s Google Classroom page. You’ll need to login with his or her username and password, but the students know that she should always be willing to share their login information with their parents/guardians. On our Google Classroom page, you’ll find much of your child’s written work, including responses to text (check out “A Chair for My Mother SAR”) and descriptive writing (look for the “Summer Snapshot” writing) projects. Feel free to look around, but PLEASE allow your child to do his or her work at school, and please resist the strong urge (Hey, I get it!) to help your child to improve the works-in-progress you see (since I won’t know what’s your child’s work and what is your work).

While not all the documents you’ll come across are intended to be graded (as some are planning tools for other purposes, others are collaborative practice, etc.), those tasks that are assessed are graded within the document itself. All grades and comments from me are written in yellow text, highlighted in black. Bold as that is, it clearly distinguishes my work from your child’s work. (Think of that color pattern as my trademark “teacher’s red pen”, if you will.)

Short answer responses are most typically assessed on a 0-1-2 point scale. Here is a copy of the rubric we use. I want to stress that 0, 1, and 2 should not be converted into a percentage. That is, I’d hate for you to think a score of 1/2 is the same as 50% (a failing grade) or that 2/2 is 100% (perfection). Rather, a 2/2 is a proficient response that includes all the elements I am looking to see. Could it potentially be improved? Of course! A 2/2 doesn’t mean that it’s perfect, just that it met expectations. Likewise, a 1/2 isn’t a failing grade. It means that the student is well on his or her way to developing a successful response, but he or she needs to improve one or more parts of the response in order to reach a 2. When I give a 1, I find myself most often asking students to give more textual support, to select more appropriate textual support, or to focus their response on a single idea and develop that idea more thoroughly. You’ll always see comments from me to explain why your child received the score he or she did.

Short answer responses are most typically assessed on a 0-1-2 point scale. Here is a copy of the rubric we use. I want to stress that 0, 1, and 2 should not be converted into a percentage. That is, I’d hate for you to think a score of 1/2 is the same as 50% (a failing grade) or that 2/2 is 100% (perfection). Rather, a 2/2 is a proficient response that includes all the elements I am looking to see. Could it potentially be improved? Of course! A 2/2 doesn’t mean that it’s perfect, just that it met expectations. Likewise, a 1/2 isn’t a failing grade. It means that the student is well on his or her way to developing a successful response, but he or she needs to improve one or more parts of the response in order to reach a 2. When I give a 1, I find myself most often asking students to give more textual support, to select more appropriate textual support, or to focus their response on a single idea and develop that idea more thoroughly. You’ll always see comments from me to explain why your child received the score he or she did.

How does your child know what goes into a 2/2 response? Good question! In our class, we use a short answer response (SAR) checklist to help students know what a thorough response looks like. Pictured to the right, this checklist lets students organize their writing. Your child should be able to explain to you what things like TTQA and “bow sentences” are.

Other areas, such as organization, sentence structure, grammar, capitalization and punctuation, and spelling are assessed using our report card scale: EMAB. A score of M is most common, indicating that a student is meeting grade-level expectations. An E means that a student has exceeded my grade level expectations. It’s important for you to understand that I don’t look at an M as falling short of earning an E, even though many families tend to feel this way. When a student’s work goes above and beyond and shows a particularly sophisticated application of the concept or skill, he or she may earn an E. Parents often ask “What does my child need to do to earn an E?” That’s really hard to answer. Allow me to provide an example. Imagine a student wrote the following description of our classroom:

There are homemade posters, called anchor charts, hanging all over from lessons. They help us to remember what Mr. Moss taught us. There are also book boxes that alternate in color between yellow and green. These hold all the great books that we get from our class library, school library, or from home. The colorful paper lanterns add even more color to our classroom.

That was a perfectly good description of our classroom, and if I was assessing the response’s sentence structure, it would earn an M. Now compare it to this response:

In our classroom, homemade posters hang all over. Called anchor charts, these tools help us to remember what Mr. Moss has taught us. The yellow and green book boxes add a splash of color to the room, as do the hanging colorful paper lanterns.

It’s clear that this second passage is a more sophisticated style of writing, and it’s sentence structure grade would be an E. But if a parent were to ask me what their student (writer of the first response) needs to do to improve, I’d have a hard time explaining it. The growth comes naturally, as a student becomes a more mature writer. As their overall use of the written English language matures, so will these discrete sentences. It’s the same with word choice. I’d hate for a parent of a student earning an M for word choice to have their child study new vocabulary words with the specific goal of earning a better grade. Instead, as the child reads more mature books with more mature word choices, it’s reasonable to expect that their lexicon will continue to grow and develop.

A grade of A means that a child is approaching the goal, is continuing to work to develop his or her skills in a given area, and has more work to do before reaching goal. An A isn’t a disaster. While I do want to avoid seeing too many A’s in a student’s work, it can serve as a focus area for your child (and perhaps for you, as you work to support your child). Finally a B means that your child’s work is below expectations and that he or she has plenty of room to grow.

I look forward to answering any of your questions about this when we meet for parent-teacher conferences. But in anticipation of our upcoming conversation, please take a moment to look at your child’s Google Classroom page so you are best informed of his or her progress in class.

Posted in Class Updates|By Jon Moss

November 9, 2017

How Written Responses are Assessed

With report cards coming home in about a week, I wanted to take a moment to encourage you to visit your child’s Google Classroom page. You’ll need to login with his or her username and password, but the students know that she should always be willing to share their login information with their parents/guardians. On our Google Classroom page, you’ll find much of your child’s written work, including responses to text (check out “A Chair for My Mother SAR”) and descriptive writing (look for the “Summer Snapshot” writing) projects. Feel free to look around, but PLEASE allow your child to do his or her work at school, and please resist the strong urge (Hey, I get it!) to help your child to improve the works-in-progress you see (since I won’t know what’s your child’s work and what is your work).

While not all the documents you’ll come across are intended to be graded (as some are planning tools for other purposes, others are collaborative practice, etc.), those tasks that are assessed are graded within the document itself. Any grades and comments are written in yellow text, highlighted in black. Bold as that is, it clearly distinguishes my work from your child’s work. (Think of that color pattern as my trademark “teacher’s red pen”, if you will.)

Short answer responses are most typically assessed on a 0-1-2 point scale. Here is a copy of the rubric we use. I want to stress that 0, 1, and 2 should not be converted into a percentage. That is, I’d hate for you to think a score of 1/2 is the same as 50% (a failing grade) or that 2/2 is 100% (perfection). Rather, a 2/2 is a proficient response that includes all the elements I am looking to see. Could it potentially be improved? Of course! A 2/2 doesn’t mean that it’s perfect, just that it met expectations. Likewise, a 1/2 isn’t a failing grade. It means that the student is well on his or her way to developing a successful response, but he or she needs to improve one or more parts of the response in order to reach a 2. When I give a 1, I find myself most often asking students to give more textual support, to select more appropriate textual support, or to focus their response on a single idea and develop that idea more thoroughly. You’ll always see comments from me to explain why your child received the score he or she did.

Short answer responses are most typically assessed on a 0-1-2 point scale. Here is a copy of the rubric we use. I want to stress that 0, 1, and 2 should not be converted into a percentage. That is, I’d hate for you to think a score of 1/2 is the same as 50% (a failing grade) or that 2/2 is 100% (perfection). Rather, a 2/2 is a proficient response that includes all the elements I am looking to see. Could it potentially be improved? Of course! A 2/2 doesn’t mean that it’s perfect, just that it met expectations. Likewise, a 1/2 isn’t a failing grade. It means that the student is well on his or her way to developing a successful response, but he or she needs to improve one or more parts of the response in order to reach a 2. When I give a 1, I find myself most often asking students to give more textual support, to select more appropriate textual support, or to focus their response on a single idea and develop that idea more thoroughly. You’ll always see comments from me to explain why your child received the score he or she did.

How does your child know what goes into a 2/2 response? Good question! In our class, we use a short answer response (SAR) checklist to help students know what a thorough response looks like. Pictured to the right, this checklist lets students organize their writing. Your child should be able to explain to you what things like TTQA and “bow sentences” are.

Other areas, such as organization, sentence structure, grammar, capitalization and punctuation, and spelling are assessed using our report card scale: EMAB. A score of M is most common, indicating that a student is meeting grade-level expectations. An E means that a student has exceeded my grade level expectations. It’s important for you to understand that I don’t look at an M as falling short of earning an E, even though many families tend to feel this way. When a student’s work goes above and beyond and shows a particularly sophisticated application of the concept or skill, he or she may earn an E. Parents often ask “What does my child need to do to earn an E?” That’s really hard to answer. Allow me to provide an example. Imagine a student wrote the following description of our classroom:

There are homemade posters, called anchor charts, hanging all over from lessons. They help us to remember what Mr. Moss taught us. There are also book boxes that alternate in color between yellow and green. These hold all the great books that we get from our class library, school library, or from home. The colorful paper lanterns add even more color to our classroom.

That was a perfectly good description of our classroom, and if I was assessing the response’s sentence structure, it would earn an M. Now compare it to this response:

In our classroom, homemade posters hang all over. Called anchor charts, these tools help us to remember what Mr. Moss has taught us. The yellow and green book boxes add a splash of color to the room, as do the hanging colorful paper lanterns.

It’s clear that this second passage is a more sophisticated style of writing, and it’s sentence structure grade would be an E. But if a parent were to ask me what their student (writer of the first response) needs to do to improve, I’d have a hard time explaining it. The growth comes naturally, as a student becomes a more mature writer. As their overall use of the written English language matures, so will these discrete sentences. It’s the same with word choice. I’d hate for a parent of a student earning an M for word choice to have their child study new vocabulary words with the specific goal of earning a better grade. Instead, as the child reads more mature books with more mature word choices, it’s reasonable to expect that their lexicon will continue to grow and develop.

A grade of A means that a child is approaching the goal, is continuing to work to develop his or her skills in a given area, and has more work to do before reaching goal. An A isn’t a disaster. While I do want to avoid seeing too many A’s in a student’s work, it can serve as a focus area for your child (and perhaps for you, as you work to support your child). Finally a B means that your child’s work is below expectations and that he or she has plenty of room to grow.

I look forward to answering any of your questions about this when we meet for parent-teacher conferences. But in anticipation of our upcoming conversation, please take a moment to look at your child’s Google Classroom page so you are best informed of his or her progress in class.

Posted in Class Updates|By Jon Moss

October 4, 2015

Learning to Collaborate

A big focus in Room 209 in learning to collaborate on tasks and explain your thinking. People often think that collaboration helps during challenging activities, and that’s certainly true. But we also have students collaborate even when they could easily complete a task independently, because the process of sharing ideas, considering other points of view, and discussing strategies and options helps students to think more deeply about a given topic. It also helps to develop collaboration skills that are, of course, critical life skills.

Last week, for example, we began working on narrative elements by focusing on the setting of stories. We read, as a class, The Purple Coat (one of my all-time favorites) and identified clues about the setting. I then modeled the process of writing a short-answer response (SAR) to identify and explain the setting of the story. We looked at the SAR Checklist as a way of remembering the elements of a successful short-answer response. Students then collaborated with one or two partners to write a similar response about The Josefina Story Quilt, which students read for homework on Monday or Tuesday. We shared some of these responses (from groups that volunteered) and discussed strengths and weaknesses, using the new fourth grade SAR rubric. (Stay tuned for some resources for parents!) On Friday, students worked independently to write their own SAR about the setting of A Chair for My Mother (which is arguably my all-time favorite children’s book). This process of gradual release supports students as we move from teacher-led learning to group work to independent application. You’ll see a lot of this style of learning this year, especially in the next few weeks as we address the remaining narrative elements.

Posted in Class Updates|By Jon Moss

February 26, 2014

Working to Improve Reading Responses (Part 1)

Note from Jon: This is the first of (probably) three posts that address reading comprehension and critical response skills. This particular post is an updated version of a message I wrote three years ago on our class website. I know it’s long, but you might find it helpful!

One of the primary focuses of reading instruction is helping students to improve the quality of their short answer responses. Unlike multiple choice, true false, or fill-in-the-blank items in which there is a clear right answer, SAR tasks create situations in which students’ success hinges on the quality of their responses, not just their accuracy. I tend to find that there are three rules that often help students to be more successful when writing their own short answer responses:

- Always show the reader that you read and understood the story or article. PROVE IT!

- Always include some sort of textual support to explain your answer.

- Read the WHOLE question! Answer the WHOLE question!

Can you tell what the big trouble spots are? All three rules include the idea of needing to fully address the question by including relevant story details. Frequently, students lack the necessary supportive evidence from the text to reinforce their answer. As I often remind the students, any SAR question faced during reading has one main goal: To determine if the student understood and can interpret what he or she has read. If the student’s response lacks specific detail from the text, the reader has no way of measuring the student’s understanding. Take, for example, the following question and answer:

Question: What two questions would you ask the author of this article?

Answer: I would ask her why she chose to write about insects and what kind of insect is her favorite.

At face value, this response looks like it successfully answers the question – and in all fairness, it does. But while the question does not explicitly require students to integrate information from the article, this (fictional) student’s failure to do just that leaves us with a weak answer that does not show any understanding of the story. Both of the questions that the student suggested in his or her response show only a cursory understanding of the text: the story is about insects. There is no evidence of any in-depth understanding. This alternate response shows more in-depth comprehension by including details from the (pretend) article:

There are two questions that I would ask the author. First, I would ask her “Why are centipedes called centipedes if they can actually have between 20 and 300 legs?” Centi means “hundred,” so I would expect a centipede to have 100 legs. I would also ask “Are insects with exoskeletons larger than those with skeletons inside their bodies?” I’ve never seen a large insect before.

Notice a few particular strengths with this response. First, the student clearly wrote two questions – ending in question marks. (Yup, that matters!) Second, the student’s suggested questions include appropriately used terminology from the text (centipedes, exoskeletons) and concepts from the text (20-300 legs, meaning of centi, exoskeletons are outside the body). By including relevant details from the text, the student has shown that he or she is able to read and understand the text and that they can evaluate information in order to use the most relevant details as supportive evidence. This is a strong response.

This type of activity is hardly new. Students have been going “full-steam” on short answer responses since the start of third grade, if not earlier. Our expectations for short answer responses don’t change much from year to year, minimizing the “moving target” problem for kids. So why do some students continue to struggle? I see three possible causes:

- Some students are having a genuinely hard time. This describes the student who sees the question, thinks about what the best possible response could be, but for any number of reasons, he or she is not crafting successful responses. The student may not be struggling with the skill, per se, but he or she may simply have yet to master the grade-level expectations that go with the skill of writing a short answer response. I’m continuing to work with students on an ongoing basis to help them to strengthen their skills.

- Sadly, some students are unsuccessful because they simply did not carefully read the question being asked of them. Consider the two part question: “Do you agree with Laura’s decision at the end of the story? What advice would you give her so she could solve her problem without hurting Lester’s feelings?” A student could write an outstanding response about why they do or do not agree with Laura’s decision, citing lots of support from the text. But without addressing the second part of the question, the response falls short, and so will the score. Unfortunately, it’s not uncommon for responses to be more off-base than the example I’ve cited in this paragraph. Sometimes kids write an answer that may be well-crafted and thorough, but it may also be entirely irrelevant to the question asked, and again, points cannot be given.

- The most disappointing cause of difficulty is when students simply do not appear to be working with their best effort and focus. This is not a lack of understanding or mastery. Rather, in this situation, students may quickly write a cursory response that lacks detail or support because they chose not to work to their potential because, perhaps, they hurried through their work. These responses do not show a thorough understanding of the text, even though the student may truly have a high degree of comprehension. Convincing students of the need to put more thought and effort into their work is very challenging, because it’s a decision they need to make for themselves. No amount of prodding from you or from me will make it happen. Rather, they need to choose (hopefully with our help) that it’s time to bring their proverbial “A-game” to class. I’m bringing this up to you en masse for two reasons: First, I think that all students can benefit from a reminder about the importance of doing their best possible work. All of us, every now and then, fall short of this, so some helpful encouragement is valuable. Second, in some cases, I see this as a behavioral issue – if a student is choosing not to put in their best effort, despite having been reminded of the importance of doing so, they are not following directions and are not showing responsibility. That’s something I hope we can tackle together.

At the end of this week, your fourth grader will bring home his or her literacy binder for your to review over the weekend. In it, you will find several new work samples, many of which are short answer responses. As you review your child’s responses, look at their use of evidence and see how it influenced their score. (As a reminder, short answer responses are scored out of four possible points, with a goal of three points.) Conferences are coming up in a few weeks, and I look forward to talking with you more about this.

In my next post, I’ll share some strategies for how students can carefully select the most helpful textual evidence to support their responses.

Posted in Class Updates, Learning Resources, Reading|By Jon Moss